I blogged last week about the profligate and sensitive Tupou II, who almost lost his kingdom of Tonga to Britain. The Treaty that Tupou II was forced to sign with the British in 1900 surrendered Tonga's foreign affairs to London, but at least kept colonial administrators out of the Friendly Islands.

Cakobau, the first and last king of Fiji, was less fortunate than Tupou II. In 1874, after a reign of only three years, he found it necessary to cede his kingdom to Queen Victoria.

By 1874 Cakobau believed that if he did not give Fiji to Britain the country would be divided between Americans and Tongans. In the hills outside his capital of Levuka American planters and their Australasian allies had formed a branch of the Ku Klux Klan, and were busy terrorising indigenous Fijians and importing slaves from the New Hebrides and Solomons to work on their cotton plantations. Many of the American planters were southerners who had been ruined and exiled by Lincoln's army, and had decided to build a new Confederate state in Fiji.

On the Lau archipelago, which runs from north to south along Fiji's eastern margin, a Tongan warlord named Ma'afu had set up his own kingdom, using warriors and colonists imported from his homeland. As a young man Ma'afu had led a ferocious Tongan raid on the New Hebridean island of Efate, and he had retained his enthusiasm for war. From the fortified village of Sawana on the island of Vanua Balavu, near the middle of the Lau group, Ma'afu aimed expeditionary forces at Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. His Tongan troops won victories for Cakobau's enemies, and Ma'afu began to believe he could capture Levuka and become king of all Fiji.

There was a precedent for Ma'afu's Fijian adventures. In the late Middle Ages a Tongan Empire despatched governors to and took tribute from Samoa, Fiji, 'Uvea, and Rotuma, and sent raiding parties as far west and north as the Solomons and Tuvalu. Like his relative Tupou I, who had unified and Christianised Tonga in the 1830s and '40s and would reign until the '90s, Ma'afu dreamed of restoring the

empire of his ancestors.

With its chaotic army, handful of quarrelsome civil servants, and incoherent laws, Cakobau's kingdom must have seemed no match for Confederate slavers and Tongan imperialists.

Back in April I found Cakobau's flag and one of his cannons near the back of the Fiji National Museum in Suva. The flag was pinned to a wall like the wing of some long-extinct bird, and the cannon's throat was dusty. I have never been a monarchist, but I found something poignant about these relics of a doomed king. I thought about some of the last lines in

Richard II, Shakespeare's tribute to another ill-starred monarch:

For God's sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings;

How some have been deposed; some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed...

Ma'afu may have helped defeat Cakobau, but he did not conquer Fiji. As John Spurway shows in his recently published, massive, and ultimately melancholy book

Ma'afu, Prince of Tonga, chief of Fiji, the master of Lau became an anachronism after the Union Jack rose over Fiji. A warlord without any wars to fight, Ma'afu was coopted by the British, and became a harmless governor of the archipelago he had conquered.

Tonga still contains a few irredentists, who share the nineteenth century dream of a revived empire. In 2014 a noble named Lord Ma'afu, who at the time had a cabinet post in Tonga's government,

suggested that Fiji return the Lau Islands to his country in 'exchange' for a couple of uninhabited, half-submerged reefs. Fiji's media and politicians were unimpressed.

At about the time Lord Ma'afu was asking for the return of Lau, the Nuku'alofa-based rapper Jimmy the Great was having a big local hit with a song called

'Pacific Conqueror', whose lyrics mixed up faux-gangsta braggadocio with allusions to the empire built by Tonga's ancient kings. 'Pacific Conqueror' probably didn't make Jimmy a great number of fans in Suva or Apia.

The Tongan monarch still appoints a noble to represent the Lau group, and Tonga's Free Wesleyan church still sends a minister to the group. Today, though, Fiji is far bigger than Tonga, and outpunches its old rival economically and diplomatically. Lau Islanders look west to Suva, rather than east to Nuku'alofa. Out of Lau's scores of villages, only Sawana remains culturally Tongan.

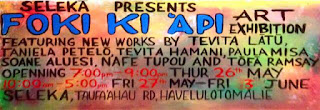

A few days after visiting Fiji's museum I found this poster on a street near the centre of Nuku'alofa, It advertises a fundraising campaign for Sawana, which it hails as 'the only remaining Tongan village in Fiji'. Like the rest of Lau, Sawana was devastated last year by Cyclone Winston. The Free Wesleyan Church where Tongan hymns are still sung was shattered, and iron flew off house rooves and into the old war-ditch that still separates Sawanans from their neighbours.

It is not surprising that a campaign to help rebuild Sawana has appeared in Nuku'alofa. For some Tongans the village is the symbol of a lost kingdom, and a lost empire.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

.jpg)